An analysis of replacement-level immigration in Australia

It’s not too late to reverse the trend of white demographic decline

Summary

This article demonstrates that since the start of the twenty-first century, successive Australian governments have overseen the implementation of large-scale replacement-level immigration.

Replacement-level immigration remains a taboo issue in Australian politics and the mainstream media. This suggests a bipartisan agreement between the major political parties to keep large-scale non-European immigration off the political agenda.

In contrast, political parties, journalists and demographers in the UK and the United States openly discuss the ramifications of white population replacement.

The Oxford Professor of Demography David Coleman estimates the white British population would cease to be the majority in the UK by the 2060s. And the United States Census Bureau estimate European Americans will become a numerical minority by 2045.

Similarly, in Australia, if mass non-European immigration is not halted and Australia’s fertility rate remains at sub-replacement level, Anglo-Celtic Australians will eventually become a numerical minority in their own nation.

Replacement-level immigration is driven by the economic, political and demographic objectives of both the Liberal-National Coalition Party and the Australian Labor Party.

The demographic transformation of Australia began in the 1970’s with the dismantling of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (Cwlth). This opened up migration flows from the Asia Pacific Region.

However, replacement-level immigration began to accelerate from the early part of the twenty-first century. The Coalition government (1996-2007) implemented a radically “new immigration system” for Australia.

The terms replacement migration and replacement-level immigration are interchangeable in this article.

What is replacement migration?

In the year 2000 the United Nations Population Division released a report titled: “Replacement Migration: Is it a Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations?”

The report estimated the volume of migrants required to offset the effect of low fertility and high life expectancy over the period 1995–2050 for eight countries: Germany, Korea, France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, Russia, and the United States. Two regions are also included: Europe and the European Union.

The report had a “significant impact in academic and civil society. It’s approach consisted of estimating the migration volumes required to mitigate the effects of population decline and ageing.”

The replacement migration report is often taken as a recommendation for future population policies. It led to a broad-reaching debate and was heavily criticised by several authors. “The major critique pointed to the exceptionally large number of migrants required to achieve the projected targets.”

It presented estimates of the replacement migration needed to: “(a) maintain the size of the total population, (b) maintain the size of the working-age population (aged 15 to 64), and (c) maintain the potential support ratio (PSR). The ratio of the working-age population (aged 15 to 64 years) to old-age population (65 years or older).”

The replacement migration report concluded that:

“The levels of migration that would be needed to prevent the countries from ageing are of substantially larger magnitudes. By 2050, these larger migration flows would result in populations where the proportion of post-1995 migrants and their descendants would range between 59 per cent and 99 per cent.”

Almost 25 years since the UN replacement migration proposals, studies and debates continue to focus on the goal of the potential support ratio. The reason this remains a highly controversial issue is the replacement migration flows necessary to maintain the PSR would eventually “displace the original population from its majority position.”

Over the past 20 years, western nations have increased net overseas migration (NOM) to record levels. The huge migration inflows of non-European migrants into countries such as the UK and Australia have resulted in large-scale demographic replacement. The economic argument for replacement migration is now overshadowed by the detrimental effects it’s having on social cohesion and social trust in western nations.

A study by demographers in 2019 revisited the UN estimates for replacement migration. The demographers found that the required replacement migration for the basic goal of sustaining total population size in the UK, was always overtaken by the magnitude of incoming migration flows between 1996 and 2015.

Moreover, “the actual migration greatly exceeded the number required to keep the working-age population stable in the United Kingdom (more than 4 million vs. less than 1 million required).”

Due to the very large increase in NOM in the UK, Oxford University Professor of Demography David Coleman estimated the white British population would cease to be the majority by the 2060s. Therefore, it’s hardly surprising replacement-level immigration remains a highly emotive issue in the UK.

Similarly, the United States Census Bureau estimated that by the beginning of 2045, European Americans are no longer projected to make up the majority of the U.S. population.

Professor Coleman adds, “it’s already well known that [immigration] can only prevent population ageing at unprecedented, unsustainable and increasing levels of inflow, which would generate rapid population growth and eventually displace the original population from its majority position.”

As is demonstrated throughout this article, Australia has been on the trajectory of population displacement for many decades.

The next section explores the initial stage of non-European immigration to Australia from the 1970s.

Labor and the Coalition reach a consensus on immigration policy: Australia increases migration flows from the Asia Pacific Region (1972-1999)

Australia’s immigration system has evolved substantially over the past century.

One of the first pieces of legislation passed by the Australian Parliament following Federation was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (Cwlth).

The Act provided the legal framework for the “White Australia policy” which had the intention and effect of preventing immigration to Australia by non-European peoples. The White Australia policy was dismantled in the 1970s.

In 1975 the Racial Discrimination Act was passed, which made racially based immigration selection criteria, unlawful.

Although those legislative changes aimed to open up immigration channels for Asian migrants. Non-European immigration began at significantly lower levels in comparison to the migration flows of the 21st century.

From the 1970s until the late 1990s net overseas migration (NOM) was set at a level the Australian community “could adjust to and absorb.” This is demonstrated in Chart 1 below, which shows NOM levels from 1972 to 1999. The average migration intake over that period was 83,000 migrants.

According to a report by the Productivity Commission, from the 1970’s the government management of immigration became more focused on the objective of increasing the well-being of the Australian community.

Due to concerns about increasing unemployment, the planned immigration quota was reduced in the early 1970s. And by 1975, the net intake was around 45,000, the lowest it had been since World War II. Net overseas migration fell further to around 20,000 in 1976 (Chart 1 below).

The natural population increase remained consistently higher than NOM from the 1970’s to the late 1990’s. This is illustrated in Chart 2.

As Chart 1 demonstrates, from the early 1970s to the late 1990s, the main parties were committed to maintaining a moderate level of NOM.

Throughout that period Australia's migration program included the social objectives discussed above. This helped regulate migration flows. Consequently, over these 3 decades NOM was more or less maintained at under 100,000 migrants per year (Chart 1)

However, the increase in Asian immigration began to accelerate and “by the 1980s … [Australian Historian Geofrey Blainey] noted that Australia’s immigration policy, gives the tiny Asian portion of the Australian population four of every ten migrant places.”1

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Historical population. Released 16/07/2024)

The following statement demonstrates the Coalition and Labor reached a political consensus to significantly increase migration streams from non-European nations:

“In 1993 [Bob] Hawke indicated that he and his predecessors on both sides of politics had adopted a bipartisan policy – an ‘implicit pact’ – to impose non-European immigration on Australians despite the public not endorsing the policy. They had done so by keeping the issue off the agenda.”2

To this day Australian politicians refrain from having an open and honest debate about replacement-level immigration. Even though Australians can observe, replacement migration is destabilising and transforming the Australian population.

The pressure is mounting for an open and frank political debate about replacement-level immigration, as more voices air their reasonable concerns about demographic change in Australia:

“If white identity continues to be suppressed, then mass replacement-level immigration [in Australia] is likely to continue until there is no white majority or sizeable minority left to sacrifice.”3

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Historical population. Released 16/07/2024)

During the period that a Labor federal government began dismantling the White Australia policy, the 1971 Census revealed that over 90% of the Australian population were of British ancestry.

Two decades later, the 1991 Census revealed that from 1981 to 1991, the fastest growing birthplace groups were from South-East and North-East Asia and Oceania.

From 1972 to 1999 the net intake of non-European migrants increased considerably, but the levels were smaller scale, compared to what occurred since the early part of the 21st century.

The average population growth from 1972-1999 was 205,000 people. The population increased by 5.74 million, over 50% of this comprised natural population increase.

The implementation of Australia's new immigration system: The Coalition turn on the immigration accelerator

“The year 2001 was a hugely significant one for Australia.”4 This is the opening sentence of a book titled Population Shock (2021). The author is Abul Rizvi, a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007.

In that opening sentence, Rizvi is referring to the implementation of Australia’s new immigration system in 2001:

“The new system was implemented on 1 July 2001. In doing so, we were looking to entirely overhaul the size and shape of Australia’s migration system. Bringing in younger people...deliberately welcoming them to become part of a new country... If it worked, we expected it would significantly slow the rate of population ageing and push back the day that deaths would start exceeding births in Australia.”5

From 1995 to 2007, Rizvi managed Australia’s migration program. “He is a frequent media commentator on population and immigration and their impact on Australia’s economic direction.”6

(Image: Abul Rizvi the former manager of Australia’s migration program (1995- 2007))

Rizvi refers to the overhauling of Australia's immigration system as a “A Quiet Revolution.”7 He was a key immigration policy adviser to former PM John Howard and Immigration minister Philip Ruddock.

An article by Australian economist Cameron Murray and journalist Misha Saul argue that Rizvi was the guy “who persuaded former Prime Minister John Howard and the Liberals to turn on the immigration gasket in 2001…Rizvi’s conception of his job seemed to be pump immigration to slow down population ageing because fertility is declining. This has a name for it: managed decline.”

Perhaps a more accurate name for slowing down population ageing is replacement migration. This is exactly what has occurred over the past 2 decades to offset projections of population decline and below replacement fertility.

The regulatory changes driven by key immigration bureaucrats such as Rizvi established replacement migration as a major feature of Australia's new immigration system.

The UN replacement migration report did not include population projections for Australia. Nonetheless, Australia was experiencing the same demographic issues as other western nations. Namely, a sub-replacement fertility rate and the possibility that population growth would begin to slow down over the coming decades.

Rizvi explains in Population Shock that the Immigration Department commissioned Australian demographers to provide estimates of the migration volumes required to slow down population ageing:

“I convinced Minister Ruddock to commission research on our long-term population future. Professor Peter McDonald of the Australian National University, now the pre-eminent voice on population policy in this country, and his colleague Dr Rebecca Kippen did the research for us, which was published in 1999.”8

Professor McDonald is known for his pro-mass immigration stance.

This is pointed out by Australian economist Leith van Onselen who revealed that McDonald consistently opposes politicians that propose making cuts to immigration: “McDonald attacked Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s tiny cut to Australia’s permanent migrant intake to 160,000.” In 2018, McDonald argued that “a net immigration intake of around 200,000 people a year is required to offset an ageing population and maximise per-capita GDP.”

Leith van Onselen is also critical of Abul Rizvi, arguing that Rizvi “has shown a lack of judgment and rigour by focusing on the temporary impacts on population ageing and using the myopic and contradictory research of Peter McDonald to advocate for high immigration.”

However, as Chart 4 below reveals, the volumes of replacement-level immigration have now reached unprecedented and unsustainable levels in Australia.

The statistics don’t lie: Replacement-level immigration is occurring at scale and pace

Government agencies and private think tanks are in the business of generating long-term demographic projections based on current trends and planning accordingly.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics conduct population and demographic projections at 5-year intervals. Demographic modelling enables politicians and immigration bureaucrats to analyse the racial and ethnic make-up of Australia and the projected demographic change over future decades.

As discussed above, the implementation of Australia's new immigration system was primarily driven by demographic objectives.

However, replacement migration is having a real detrimental impact on Australia’s founding Anglo-Celtic ethnic group. The demographic decline of white Australians has occurred at scale and pace over several decades. Yet Australia’s media and politicians have avoided any meaningful discussion about the downside of demographic replacement in Australia.

The 2021 Census revealed that only 51.7 % of respondents to the ancestry question were of British ancestry. Compare this to the 1971 Census, which revealed that over 90% of the Australian population were of British ancestry.

In just half a century Anglo-Celtic Australians have been displaced from a substantial majority and are close to becoming a numerical minority (less than 50% of the population) in their own nation. This is a diabolical situation for Anglo-Celtic Australians:

“In Anglo nations, there are well organised and well-funded pressure groups that attack anyone who advocates limiting immigration to protect national identity...This suggests that the end point, if not the intention, of these policies is the reduction of Anglo or white majorities until they become minorities in their own countries.”9

The large-scale replacement of Anglo-Celtic Australians remains a highly controversial and unresolved issue. The pressure will continue to build for a frank and open debate about mass replacement-level immigration in Australia:

“Prior to the 1970s, Australia had immigration policies that favoured whites, keeping them an overwhelming majority of the population. These policies were removed by powerful progressive elites without support from the majority who have never been allowed to vote on them.”10

In the early 2000s, Coalition politicians were surely given some indications by policy advisers that the displacement of European Australians was inevitable as a result of significantly expanding non-European migration flows.

Australia’s new immigration system was implemented during a period when Australia’s Total Fertility Rate (TFR) was at sub-replacement level. Australia’s TFR has remained below replacement since the 1970’s.

As the Oxford Professor of Demography David Coleman points out:

“Any population with sub-replacement fertility that attempts to maintain a given population size through immigration would, accordingly, acquire a population of predominantly, eventually entirely, immigrant origin.”

Mass non-European immigration is driving the trajectory of demographic change in Australia.

In 2004-05 the net inflow of non-European migrants reached 66% or 106,000 of the total migration inflow. By 2018-19 non-European migrant flows more than doubled to 237,000 equating to 93% of the total net influx. By 2022-23 the net inflow of non-Europeans reached a record 491,000 migrants, overtaken all previous records by a significant margin.

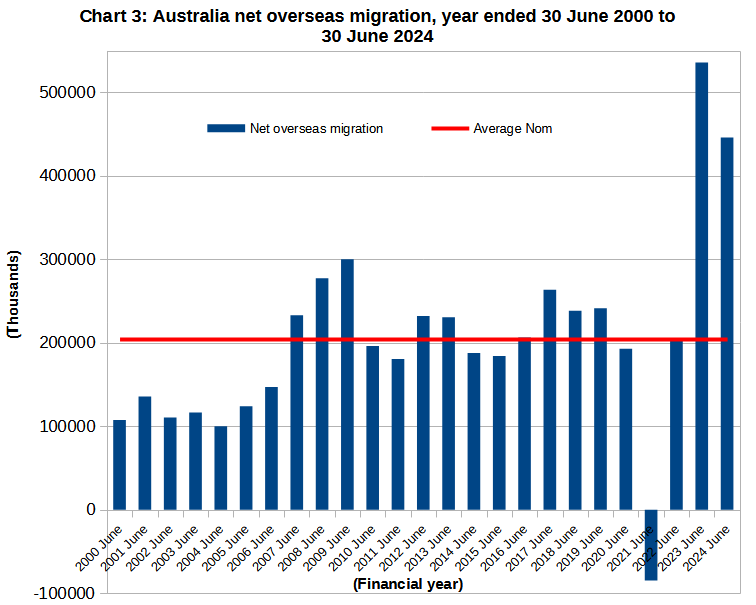

In 1998 NOM was 79,000 (see Chart 1 above). But less than a decade later the net intake had risen to over 230,000 (Chart 3). NOM nearly tripled during John Howard’s term as the Australian Prime Minister (1996-2007).

One of the main strategies the Australian government executed to expand immigration was to rapidly increase the numbers of visas issued to foreign students. Foreign students would be “allowed to apply for permanent residency. Critically, they could do this without having to go back home.”11

The following data provides an indication of the Coalition government’s reckless decision to significantly expand the foreign student visa program: In 2004 the number of foreign students enrolled in Australia was around 346,000. By 2024 this figure ballooned out to 1.1 million enrolments. Clearly the student visa program is out of control, loosely regulated and remains uncapped.

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Historical population. Released 16/07/2024)

In 1997-98 Australia's permanent migration program granted around 68,000 permanent visas. By 2006-07, this more than doubled to 148,000 permanent visas.

Chart 3 also highlights the average NOM from 2000-2024 was 204,000 migrants, more than double the average NOM for the period 1972-1999.

The huge increase in immigration over the past 20 years resulted in a much higher rate of demographic displacement, compared to the slower pace of demographic change that occurred when natural increase remained higher than NOM – from the early 1970s to the late 1990s.

Perhaps the most clear-cut demonstration that consecutive governments have overseen replacement-level immigration is illustrated in Chart 4 below. The Chart reveals the national origin of migrants arriving in Australia since the early 2000s. It demonstrates the large majority are from non-European nations.

Chart 4: Country of birth composition of Net Overseas Migration, from June 2004-05 to June 2023-24 (cumulative)

(Source; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Overseas Migration. Released 13/12/2024)

Put in a historical context, the net inflow of 3.83 million non-European migrants over 2 decades is unprecedented. Non-European migrants comprised 78% of the total net inflow. The largest group by a significant margin were migrants from the Asia Pacific Region who made up more than 60% of the non-European proportion, culminating in a migration wave of nearly 3 million people over a 20-year period (Chart 4).

In 2022-23, the natural increase of Australia's population was just over 100,000, in that same year, NOM reached a massive net gain of 536,000 migrants (Chart 3). This resulted in the ratio of new immigrants to newborn Australians reaching an unprecedented 5:1. The replacement rate of European Australians soared to a record high.

The Labor government brought in around 1 million migrants over the 2 years from 2022-2024. The statistics don’t lie. Labor have clearly demonstrated that replacement migration is not only about sustaining economic growth. It’s simultaneously accelerating the demographic replacement of Anglo - Australians.

The fact that Labor allowed in huge numbers of non-European migrants in the space of 2 years, certainly reflects their unyielding support for more ethnic diversity and a multicultural society. And there is also an electoral advantage for Labor which clearly motivates their desire to ramp up replacement-level immigration

The Australia Electoral Commision data demonstrate that non-European migrants predominantly vote for the Labor party. This was the case at the 2025 federal election:

“Demographically, Albanese built Labor’s win by wooing renters and mortgage holders, younger voters, those with a university education, middle-income earners, and constituents with an immigrant background.” Labor picked up seats with "significant Chinese - Australian populations such as Menzies (26.7 percentage points), Aston (14.1 points) and Deakin (13 points) in Melbourne, and Banks (20 points) in Sydney.

The authors of Anglophobia: The Unrecognised Hatred (2023) argue that: “The Labor Party was using multiculturalism in the form of identity politics to increase its votes among the non-Anglo, largely immigrant, population.12

The authors continue, “Multicultural policies are often aggressive towards the founding ethnic group, acting like a form of cultural warfare intended to defeat Anglos demographically, economically, and psychologically.”13

Towards a new population plan for Australia

A recent survey by The Australian Population Research Institute revealed that 80% of respondents prefer a reduction in immigration, and 27% of these voters would prefer zero net overseas migration. Only 11% of the electorate support the current high migration settings.

Australian economist Leith van Onselen points out: “Prior to the pandemic, almost every opinion poll showed that Australians do not support high levels of immigration.”

Given how unpopular mass immigration is among the Australian public. There are alternative population projections which could attract significant public support.

The Australia Bureau of Statistics produce population projections at 5-year intervals. These projections are based on assumptions of fertility, mortality and migration. The ABS use these assumptions to create 72 sets of projections. These include a zero net overseas migration series.

The ABS Data Explorer tool can be manipulated to produce population projections for political parties that are looking to develop policies based on keeping NOM at around 100,000 or lower, such as a zero NOM policy.

For example, a higher total fertility scenario assumes that Australia's TFR will rise to 1.75 babies per woman by 2027 and remain constant thereafter. Combining this higher TFR with a zero net overseas migration policy, estimates a population size of 26.4 million people by 2071 (See Chart 5 below). This projection shows a small population increase of 400,000 people by 2071, compared to the population size in 2022. This scenario demonstrates potential to minimise population loss.

It’s also feasible that Australia’s TFR could increase from the current historical low of 1.5 to 1.75 over a short to medium period.

The differences in the ABS population projections between a zero NOM and high NOM (with a constant TFR of 1.75) is enormous. The high NOM projects a population of 19.5 million more people by 2071, compared to zero NOM.

The high immigration projection display Australia’s population accelerating up to 46 million people by 2071. It’s worth noting that the Intergenerational Report 2023 revealed the federal government are considering a plan to increase Australia's population to 40.5 million people by 2062-63.

A zero NOM policy combined with a higher TFR estimates a reasonably stable population stretching out to 2071. This population size has the potential to sustain the Australian economy and maintain economic growth. This projection does not demonstrate significant population deficits.

The Australian population could be supplemented by implementing a small but high skilled migration program. This program could prioritise migrants of European descent from the socially cohesive nations of Europe the UK and North America.

The core aim of a zero NOM policy could be to put a brake on white demographic decline in Australia.

This could form part of a comprehensive migration plan, which would involve significantly cutting back on temporary migration and the foreign student visa program. There are currently 2.54 million temporary visa holders in Australia (excluding visitors).

It’s also reasonable to suggest a zero NOM policy, has the potential to free up a lot more affordable and appropriate housing for Australian families. Providing Australians with the opportunity to plan for a family.

During the period of Australia's international border restrictions (2020-2022), there was a significant decrease in rents across Australia’s capital cities. This reflected elevated supply of rental properties and weak demand because of travel restrictions and lower population growth. Large numbers of temporary migrants returned home resulting in NOM dropping to less than zero.

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Population Projections, Australia, released 23/11/2023)

Given the upward trend of non-European immigration in Australia. The level of white demographic replacement resulting from a higher NOM projection over the coming decades would be unacceptable to the majority of Australians.

On the other hand, a zero NOM projection is highly encouraging. It has the potential to be a popular immigration policy. Zero NOM has the potential to maintain social cohesion and social trust by significantly cutting back the migration inflows from countries known for radical views or extremism incompatible with Australia’s culture and national identity.

One very important aspect is that zero NOM has the potential to sustain Anglo-Celtic Australians as the majority ethnic group in their own nation.

A zero NOM policy could be applied within a migration framework that: (a) prioritises migration inflows from non-European nations with aim of bringing in the highest skilled migrants from culturally compatible nations, (b) cull the temporary migration program, which currently stands at about 2.5 million visa holders in Australia, this may result in large-scale emigration from Australia over several years, and (c) introduce a voluntary repatriation program with financial incentives and other assistance for migrants that wish to return to their homelands and set up a business etc. This list is not exhaustive.

Further research is required for a new national immigration system for Australia.

Conclusion

A Liberal-National Coalition government introduced a new and expanded immigration system in Australia in the early 21st century.

The new immigration system included policy objectives to: (a) sustain high population growth, (b) maintain high economic growth, (c) maintain the size of the working-age population, (d) slow down population ageing and, (e) offset the projected population decline, resulting from Australia’s sub-replacement fertility rate.

Since that period replacement-level immigration has accelerated. Large-scale non-European immigration in combination with Australia's sub-replacement fertility rate has pushed Australia’s founding Anglo-Celtic ethnic group closer to majority-minority status.

A zero NOM policy or a moderate migration intake of around 80,000 high-skilled migrants from the UK and Europe, is likely to have several social, cultural and economic benefits for the Australian population.

Resetting NOM to the more sensible levels of the late 20 century would be a very reasonable policy response in the current circumstances. This would significantly ease population pressures on housing, infrastructure and essential services.

References

Salter, Frank. The Voice Referendum: A Statement on Behalf of the British Australian Community (p. 23). Social Technologies. Kindle Edition.

Ibid 24.

Richardson, Harry; Salter, Frank. ANGLOPHOBIA: The Unrecognised Hatred (p. 76). Social Technologies. Kindle Edition.

Rizvi, Abul. Population Shock (In The National Interest) (p. 1). Monash University Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Ibid 9.

Ibid 93.

Ibid 2.

Ibid 5.

Richardson, Harry; Salter, Frank. ANGLOPHOBIA: The Unrecognised Hatred (p. 114). Social Technologies. Kindle Edition.

Ibid 60.

Rizvi, Abul. Population Shock (In The National Interest) (p. 8). Monash University Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Richardson, Harry; Salter, Frank. ANGLOPHOBIA: The Unrecognised Hatred (p. 124). Social Technologies. Kindle Edition.

Ibid 12.

A great and well researched article. Our replacement is not a natural occurrence, nor the result of unstoppable global trends.

It’s not inevitable. If people can move to Australia, they can also move away.